There’s something I often hear from designers at early-stage startups in my work at Designer Fund: “I wish we had more clarity around the process we use to take a product from idea to launch.” This is why I often recommend to teams and leaders that they create a process map of their ideal design process. In other words, a template that everyone can refer to as they bring a product from idea to ship.

A process map can help a growing design team scale, produce quickly, maintain brand cohesion, and make sure each individual is working on projects that come to fruition. It also helps adjacent teams like product management, marketing, and engineering know exactly how to work with design.

It starts with a simple question: What’s your ideal design process? The resulting discussion produces an artifact to circulate around the organization, such as a PDF chart, spreadsheet, task list, Google doc, or poster to hang on the wall.

But the real fruit of the process map exercise is less about the artifact and more about helping your team gain clarity. When you verbalize and visualize your ideal system, you set expectations and remove ambiguity. Without that step, people waste tons of time on projects that shouldn’t move forward or feel anxious about how to proceed at each phase.

"A process map can help a growing design team scale, produce quickly, maintain brand cohesion, and make sure each individual is working on projects that come to fruition."

I’ll discuss how you can make a process map for your design team (or any business activity that requires team cohesion). To start with, I’ll share a story about the importance of a process map from my past as a design lead at Facebook.

Design process at Facebook

It was 2008, and Facebook was swiftly expanding. We were right around our 100-million-user milestone, and our ten-person design team was hustling to keep up. We operated organically, with each designer having the autonomy to build and ship.

This naturally gave rise to some unspoken rules. For example, products that the CEO was particularly focused on needed his approval before going live. For everything else, we tended to make judgement calls. It wasn’t clear when and if to bring work to Mark Zuckerberg.

But as Facebook spun faster and faster, our loose design process started to wear at the edges. The CEO started to see too many unbaked ideas. Some features were designed in the open and some in private, which led to frustration if people found out about a product or feature only after it had shipped. And our visual language became less consistent. Details like different tab styles and color shades emerged as people hustled to get their projects out the door, and it would be unclear whether a new style was now official, or just a trial.

As more teams around the company wanted to work on projects with design, we needed a way to set expectations with them about how our collaboration would work. For example, other teams accidentally made design changes without knowing who owned Facebook’s visual design and needed to give approval—like when an engineer would alter a button style to fit what they perceived to be a unique use case exempt from our visual canon. In another example, we’d forget to tell customer support about a new launch until the day before, and they’d have to scramble to prepare for incoming issues.

All in all, when we looked at our products across the board, we’d see different quality levels and different production speeds.

When we examined what was happening, we realized a big root cause was that we didn’t have an agreed upon process that every designer, engineer, and PM could point to.

"A big root cause was that we didn’t have an agreed upon process that every designer, engineer, and PM could point to."

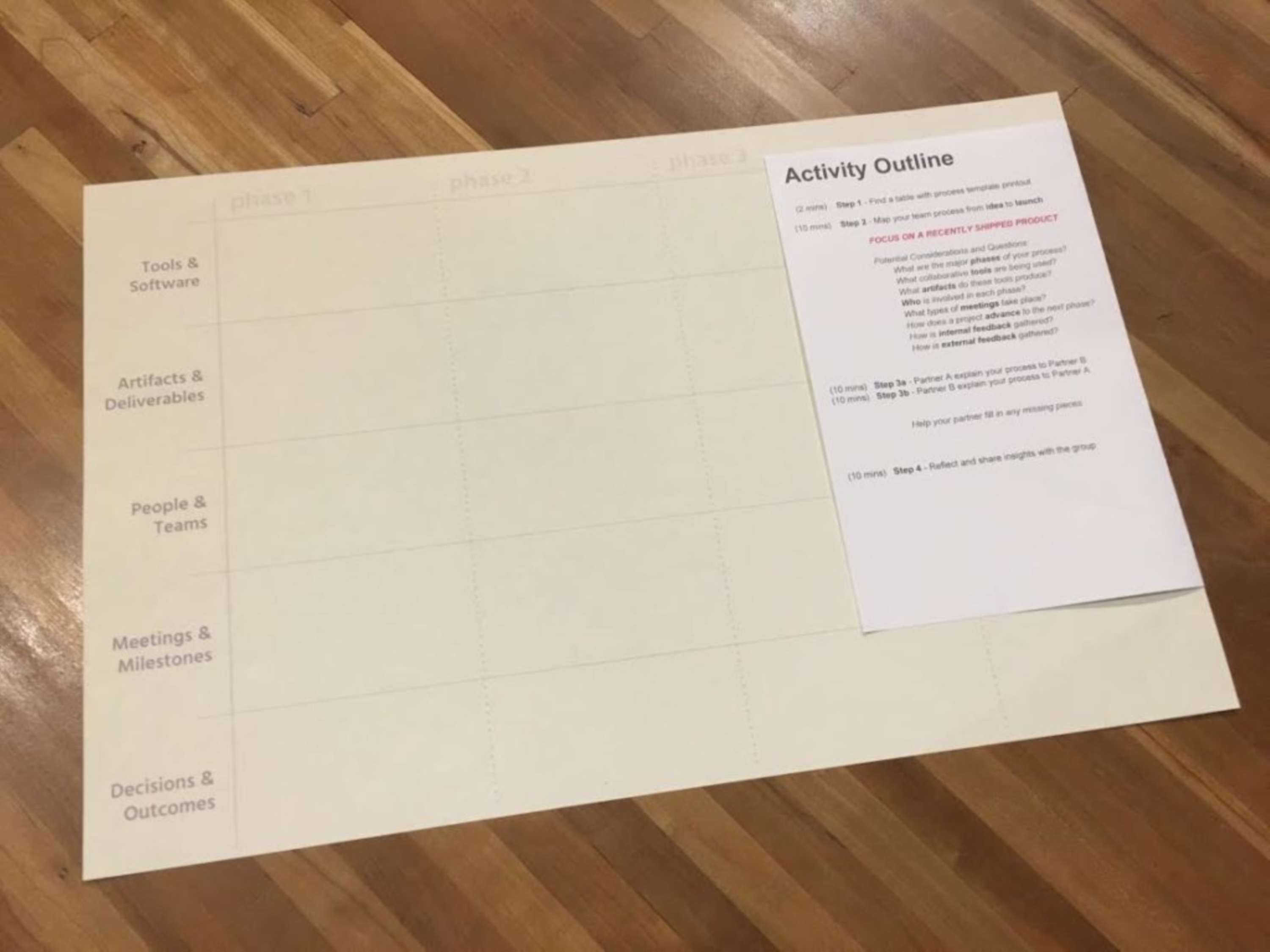

In response, we created a process map. A process map visualizes the ideal process that takes a feature from Idea to Shipped, and puts a stake in the ground about the actions, people, tools, and decisions that should be involved in each phase. There might be exceptions, but all things being equal, it’s the process everyone’s expected to follow.

Two or three designers on our team defined and visualized the perfect design process, then we all discussed and agreed on it. We turned it into a designed PDF that we could email to people around the company.

This process map exercise introduced or made official some very helpful practices. We established working groups to make sure changes received rigorous feedback before they hit the CEO’s desk, like a visual design group that would review all buttons and tabs for consistency. We knew to when to clue in a teammate from customer support (in the first meeting about a new project), and when to get legal review (usually much later). And teams that wanted to work with us could expect a kickoff meeting where we’d review their data and research.

"If teams want to survive the real world, they need built-in flexibility to accommodate compressed timelines, unexpected variables, and intuition."

As a result, we had a set of default actions that often relieved us of cognitive burdens while we worked. “Should we make a creative brief for this project?” Yes; that’s something our team officially does. “Should we show Mark?” It depends on the priority and scale of the project.

If teams want to survive the real world, they need built-in flexibility to accommodate compressed timelines, unexpected variables, and intuition. At Facebook, this happened plenty of times, such as when we got only two weeks’ notice that CNN wanted us to build a commenting infrastructure for the live stream of Obama’s 2008 inauguration.

So our go-to plan also became a baseline to measure how far we’d deviated when projects didn’t follow the process perfectly, and served as a true North to shoot for over time. It helped us ship faster, work in concert, and play nice with other teams.

Below are some ways to create a process map for your team or organization.

Elements of a process map

Process maps don’t have a prescriptive structure because they should clarify the unique steps and requirements native to your design team and company. But for illustrative purposes, your process map might use the 4 phases of Dave Merholz’s Double Diamond Model of Product Design: Ideation (Understanding customer issues and thinking about product strategy)

Definition (Further defining the strategy and project requirements)

Iteration (Prototyping and testing)

Implementation (Fleshing out and refining the solution)

For each of those phases, you can define what must be in place before moving the product forward. Specify things like:

People: How many designers need to be involved at the Ideation phase? Who needs to approve prototypes before we can implement them? When does the CEO come in?

Tools: What software and design tools are we using at each phase?

Artifacts & deliverables: What tangible or digital-tangible items will each phase produce? A creative brief? Wireframes? A recap presentation of customer interview learnings?

Meetings: What meetings should we be having? If we need to review a design with the head of product, when should that happen? Decisions & outcomes: What exactly is the data or decision we need to make before we can release a product out of the prototyping phase and into execution?