'Cited as the ultimate champion for high-potential undergraduates, The Undergraduate Awards is the world’s largest academic awards programme. It is uniquely pan-discipline, identifying leading creative thinkers through their undergraduate coursework.'

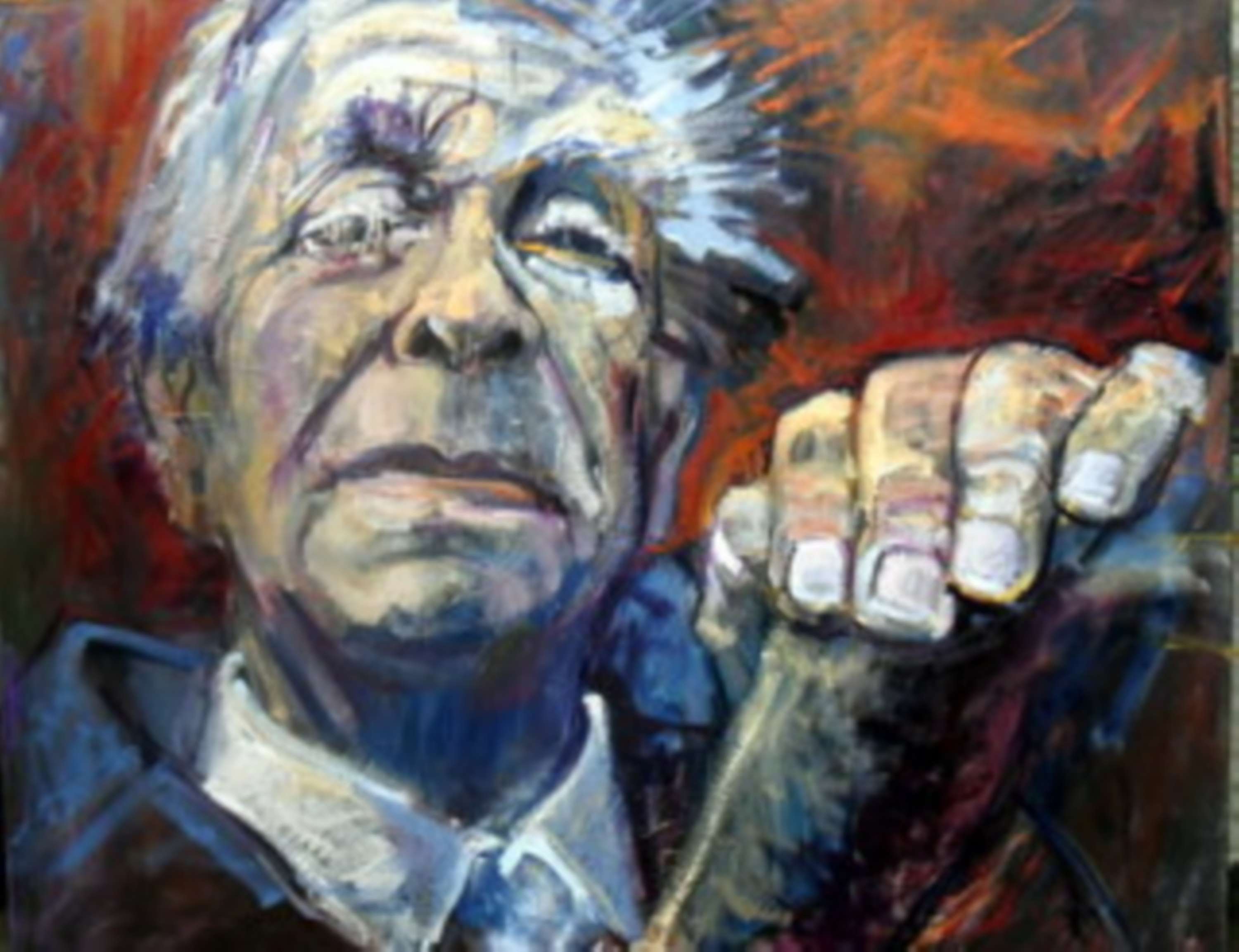

My submission, which was named Global Winner in the Non-English Literature category, was taken from my final-year dissertation on Jorge Luis Borges and translation. The following is the abstract that was printed in the Undergraduate Awards journal for 2016.

The dissertation compares existing English translations of two Borges stories in the context of contemporary translation theory, in addition to Borges's own translation methods. The entry is comprised of my introduction and my first chapter, in which I give a brief outline of translation theory and the different methods of translating literary texts. Borges's translation career, and how his theories matched his efforts at translating texts into Spanish, are also described. The chapter also covers how he incorporated translated text into his fiction.

It is argued here that fidelity to the author and to the meaning of a text are key for accurate, appropriate literary translation. It is also argued that, while Borges's translation methods were original and distinctive, they do not make for good target-language equivalence—something that is proved by Borges abandoning such methods when translating his own texts into English.

i. An overview of translation theory

Translation theory is balanced between preferring more liberal versions that focus on readability, and more literal translations, which emphasise the language of the author. These days, debate over the global status of English comes up here: should a translation read like fluent English, negating the original language? Or should it read like a translation, putting faith in the author? The preference is usually to translate into natural, readable syntax. You may lose something from the source material, but word-for-word translations don’t sound good in whatever tongue you’re translating into.

While the issue of faithfulness to the source language (the language of the original text) versus readability in the target language (the language being translated into) has always arisen in translation theory, since the mid-twentieth century there has been a tendency in English-language translations to make a text appear ʻfluent': that is, to make it seem as if it was written in English. Critics such as Lawrence Venuti argue that this entrenches the status of English as a dominant world language, while discrediting the role and efforts of translators, rendering them ʻinvisibleʼ.

There appears to be little agreement about translation practice. Should a translator embrace the global trend towards a homogenised Anglophone culture, and ensure that the translation reads like fluent English? Or are more literal translations the only true representations of writerʼs thoughts, even if the rendition is accurate but inappropriate?

Where this conflict leaves the translator is uncertain; personal preference certainly influences how a translation is received. Peter Newmark quotes William Weaver, the translator of Italian literature: ʻWhen a reviewer neglects to mention the translator at all, the translator should take the omission as a compliment to his anonymity, a real achievementʼ. However, Newmark refutes this claim, believing that this attitude promotes the lack of recognition for translators and the tendency of those in the literary world to take them for granted.

ii. Borges and translation theory

Borges was from Argentina, born in 1899 and died in 1986. He was known for his singular, genre-defying short stories. Borges’s fiction is often knowingly erudite, and borders on fantasy in its abundance of themes, ideas and settings.

However, though known primarily as an author, Borges also translated fiction from several languages into Spanish. His very first published piece, a translation of Oscar Wilde’s ‘Happy Prince’, was published in a Buenos Aires newspaper when he was just 11—and, ironically, credited to his father, Jorge Guillermo. Despite this early upset, translation was a craft that was forever important to Borges. In several languages, including French, German and Russian, the verb to translate signifies ʻto carry acrossʼ, which is precisely what Borges did with various translations, as texts he translated made their way into some of his best-loved fiction. Elements of his translation of Edgar Allan Poeʼs ʻThe Purloined Letterʼ ended up in Borgesʼs detective story ʻLa muerte y la brújulaʼ (‘Death and the Compass’), which he wrote while he was preparing an anthology of translated detective fiction with his longtime friend and collaborator, Adolfo Bioy Casares. It is also arguable that the influence of his translations of Woolfʼs Orlando and Giovanni Papiniʼs story ʻLʼultima visita del gentiluomo malatoʼ (‘The Ill Gentleman’s Last Visit’) can be seen in ʻEl Inmortalʼ (‘The Immortal’) and ʻLas ruinas circularesʼ (‘The Circular Ruins’) respectively. Indeed, ʻreal translations play a vital role in the gestation of Borgesʼs works that imagined ones do not: many of Borgesʼs translations, and those of others, are links between the works he translated and the originalsʼ.

iii. Borges the translator

But what of Borges’s own translations? In a lecture as late as 1953, he described himself as a translator first and as a writer second. Nonetheless, Borgesʼs opinions on translation were far from traditional. Where some translators follow the language of the original text closely, he proposed a much freer role for the translator, and rejected the idea that any translation is intrinsically inferior to source material. Furthermore, there is a sharp contrast between Borgesʼs practice of translating his own texts—which he did, with American translator Norman Thomas di Giovanni—and those of other writers (of whose texts he frequently altered the register, syntax and style, in order to vindicate himself, the translator). Borges’s reworked translations with di Giovanni read well, but are very faithful to their originals. That Borges could be so carefree with other people’s fiction but cautious with his own leads us to note what English poet John Dryden said on translating Latin writer Ovid: that if while translating he doesn’t pay attention to the original verse, his translation is no longer Ovid.

There appears to be no easy answer to the central tension of fluidity versus fidelity in translation. The translator can thus be left frustrated by the shortcomings of their craft, or fascinated and energised by its possibilities. Good translators should strike a balance between readability and respecting the original text and its author. Borges, however, thought that new versions of, and variations on, old classics were central to literature’s ongoing appeal. He was hardly a model translator, but the Argentine’s belief that no translation can be considered ‘definitive’ is interesting in itself—if only to detract from the pessimistic idea that translation is, by nature, doomed to fail.

Borges, Jorge Luis, Obras completas (Complete Works), 3 vols, (Buenos Aires: Emecé, 1964)

Bellos, David, Is That a Fish in Your Ear? Translation and the Meaning of Everything (St Ives: Penguin, 2012)

Bloom, Harold, The Western Canon: The Books and School of the Ages, New York: Harcourt & Brace, 1994

Christ, Ronald, The Narrow Act: Borgesʼ Art of Allusion (New York: Lumen Books, 1995)

Cosgrove, Ciaran, ʻLanguage and Translationʼ, The Poetry Ireland Review (No. 18/19, Spring 1987)

Kristal, Efraín, Invisible Work: Borges and Translation (Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 2002)

Leone, Leah Elizabeth, ʼDisplacing the mask: Jorge Luis Borges and the translation of narrativeʼ, PhD (Doctor of Philosophy) thesis, University of Iowa, (2011) http://ir.uiowa.edu/etd/1011, [accessed 27 November 2014] Newmark, Peter, More Paragraphs on Translation (Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, 1998)

Paz, Octavio, Un poema de John Donne: traducción literaria y literalidad (A Poem by John Donne: Literary Translation and Literalness (Barcelona: Tusquets, 1990)

Venuti, Lawrence, The Translatorʼs Invisibility: A history of translation (London: Routledge, 1995)