Published by Frame Magazine, Sept 2015

The following text resulted from an interview with artist Job van Lieshout and was published as part of the series 'What I've Learned' by Frame Magazine. The interview touched on experiences that influence his work today and broached the issue of the political and socially critical character of the work by Atelier van Lieshout.

I've always had the idea to start a revolution, to throw over the world. I don't have a political background. I just wanted to start a revolution. I used to be a communist and anarchist but, you know, that was when I was about fifteen.

I started art school when I was sixteen. That was in 1980. This was full on punk, squatting, big crisis, a lot of idealism, there was a very strong left-socialist movement, demonstrations and things like that. At the time, everyone was a communist. I don't know anyone who was not a communist, then. Apparently, that was a cool thing. My older brother also influenced me. My family was just middle-class.

Squatting became difficult lately, but I still live in a squat. Or rather, this building [where my private atelier and home is situated] started as a squat and was legalised later. Today, I express my thoughts through my work, which is still critical. I wouldn't call it political. It's about social criticism.

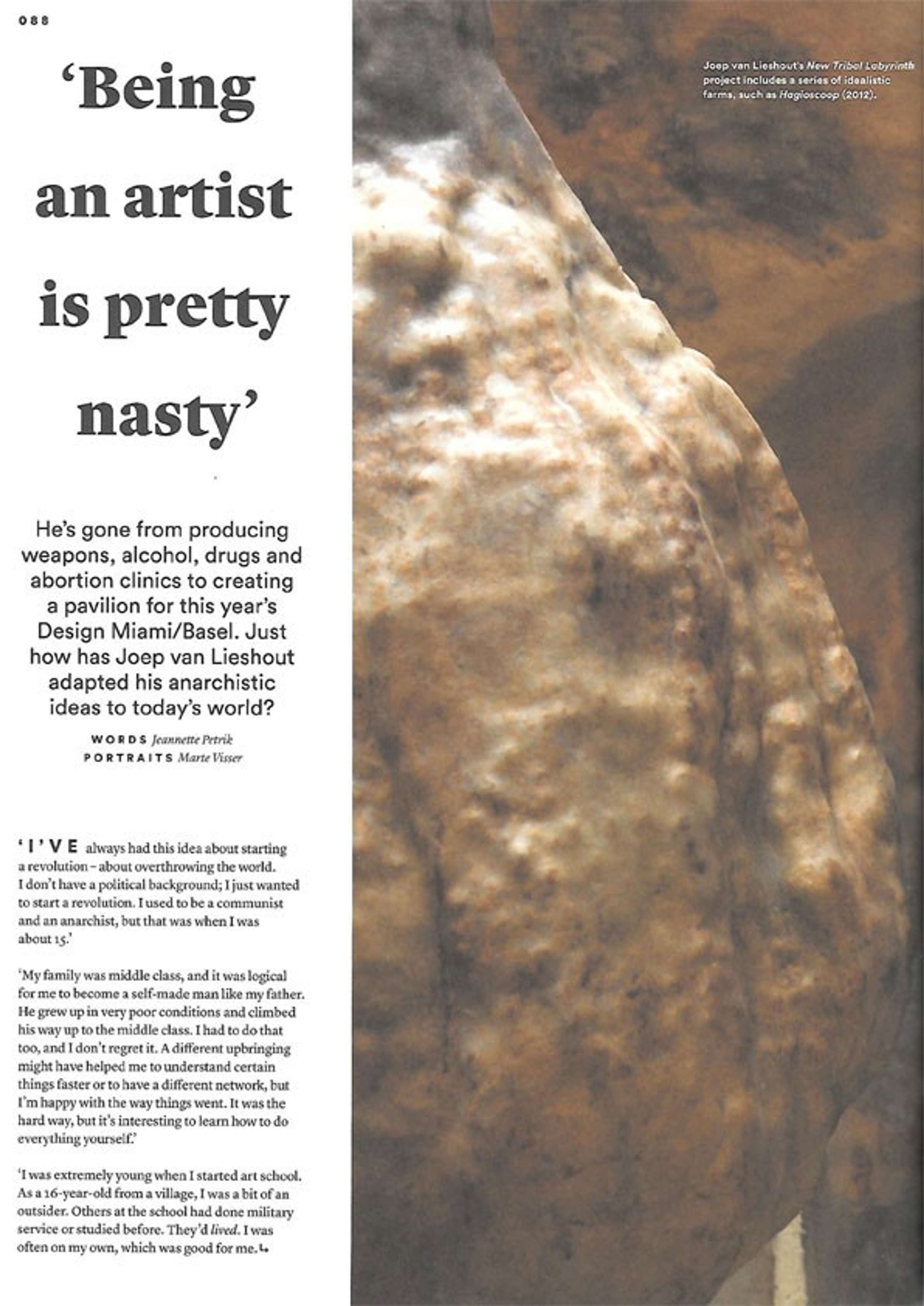

My work is a non-political engagement to society. I did a project called 'SlaveCity', which portrays the worst, rationalised and hyper-organised society, in which Excel sheets dictate life. Now, I'm working on a project called 'New Tribal Labyrinth'. I'm reinventing the Industrial Revolution by going back to the roots of modern production, to the blast furnaces with which you make anything from casseroles to heavy machinery. You don't use them to make iPhones or other lifestyle products that you find in Frame Magazine. Looking at the world today, this is a strong statement that has to do with the abundance of everything. Behind the project lies a very romantic idea about the importance of life.

In 2001, I created a free state [at Atelier van Lieshout] here in the harbour. Now, we do things differently. We became bigger and better, and better organised. We bought two buildings next door to set up an exhibition space and to start an artist residency. We also collaborate with the food garden next door. We try to improve the area on a local and international level by implementing my practice. What I'm really good at is making artwork, so I'm creating a very megalomanic place. By making art, I communicate my ideas. They speak about our society and about how we organise it. So, my art makes people think, hopefully.

[To set up the free state,] we basically squatted a piece of land and then started building housing, restaurants, a workshop for weapons and bombs, an abortion clinic and all kind of stuff. We just created it. We built things on the squatted piece of land and wanted to be independent. We had a power plant and water purification systems. We also decided that there we were not going to have any rules on that piece of land. You could do whatever you wanted.

I didn't see people going crazy, fucking dogs or anything like that. Some babies were born, but nothing really bad happened. It was more like a party, but I felt like I was only talking to press and lawyers which I don't like to do. Nine months is quite long for an independent state. If you look at the history of utopian states that's kind of average.

At that time, I really wanted to create a free state. I saw it as a development towards self-sufficiency. Then, it was necessary as a rebellious act. Nowadays, I don't want to express the same thing as then. So, there is no necessity not to ask for permits. In reality, of course, it's far easier to ask for permits than not to. It's just a different time now. At the time of the free state I was producing weapons and alcohol, drugs, medicines and abortion clinics. That was a different time. Now, our abortion clinic has a permit, for example. We made it for the organisation 'Women on Waves' who used it for some years. Now, they just send people the pill by post, so they gave it back to us. So, we have an abortion clinic. It has a permit and is officially tested.

Activism is very one-dimensional, I think. There are no deeper layers to it. You might say “I'm against seals being butchered for fur coats”, but there is no deeper layer. In that statement there is nothing that makes you think about contemporary life. It's very one-dimensional. With art, you can say “I don't like seals being slaughtered but I like naked women in fur coats.” You can say that and point towards the complexity of things. You can portray many different messages and layers, which then create something complex. The conflict of meaning, of interest or ideology, that is what makes art interesting. That's why art is art. I'm not one-dimensional. I'm multi-dimensional.

I was extremely young when I started art school, I was sixteen and came from a village. I was a bit of an outsider. Others had done military service or studied before, they had a life before. So often I was on my own, which was good for me. If I wouldn't have done art school I would have studied physics, probably. Then I would have become an inventor. I like to think about how to improve things. I'm never satisfied and always think that things could be different. I might have the idea that if I do something it will end up being perfect but it never turns out like that. Being an artist is pretty nasty. There's a lot of insecurity, there's a lot of competition and financially it's very hard to survive. I mean, I'm doing well but still it's a bitch, you know. So, if you know that you'll have these kind of difficulties you better make sure that the process and the work itself is exciting.

[Growing up in a middle-class family,] it was very logical that I had to be self-made like my father. He came from very poor conditions and climbed up to middle-class. I had to do that, too. I don't regret this either. If I had come from a different background maybe I would understand certain things faster or have a different network of relations but I'm happy with the way how things went. It was the hard way but it's interesting to learn doing everything yourself. Now, more and more people get involved in the management of the studio and I'm stepping back from the management so that I can focus on being an artist and visionary. As it is now, I'm in control and I can do whatever I want. Today I can do this, tomorrow I can start a big industrial meat farm if I want to.

I would have liked to marry a billionaire, to have unlimited resources so that money would never be an issue. Then I could buy a steamroller and destroy a city and build beautiful high-rises there, or something. Of course, the struggle is important to go through... but this is a company so we need to have cash every month to pay everyone. In reality, I like to make things like the blast furnace that nobody wants to have. That kind of piece is just costing money and it will never sell. I would just do different things, I guess. Maybe I'd also become lazy, I don't know. I don't have regrets because I'm blessed with a terrible memory. Even the good things I forget. It's as if the bad things didn't exist.