Artist Carey Young has chosen 19 artists for Bow Arts’ annual Open Show, with a call for works that respond to “our current political moment”. Choosing from some of the charity’s near 500 studio holders, many of whom are showing new pieces, the result is a selection of artistic works which engage with varied political themes including politics, migration, gender identity, borders and climate change; poignantly and critically addressing some of today’s most pressing cultural conversations. These statements – written by the artists – explore how their work engages with these themes.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Bernie Clarkson | A cry for Something to be Done

My painting was part of a project that looked to respond to the news in a local daily free paper. Each morning I would go into my studio and begin my day by painting a striking image from that day’s paper. My initial motive was to get my working day started quickly, trying not to prevaricate or worry about the end result. I was keen to become more efficient with regard to mark making, colour mixing and style development.

The number of paintings quickly grew and I soon realised that the more political images had the most impact and engaged me in the work. Social issues, war, weather extremes, law enforcement…the daily papers presented many issues to reference in my work. The work took on a life of its own and a small exhibition of 40 of the paintings arranged in a grid reinforced the benefits of this practice.

While my painting is not by intention political, I am always seeking to suggest a level of something ‘other’ in my work and I was fortunate to be able to develop this idea when I wrote my MFA dissertation ‘Fear in the Imagined landscape’.

Our current political landscape has and is creating a sense of fear as we imagine what may lie ahead and this painting is my response to a collective concern.

Lindsey Mclean | Salome on the Underground

In my painting Salome on the Underground I am questioning traditional notions of gender, with a particular interest in the roles prescribed to female figures in narrative painting, informed by Pierre Bourdieu’s theory of ‘symbolic power’. In suggesting that those who wield power in society do so partly by constructing and upholding symbolic status (rather than solely through ownership of financial capital), Bourdieu lays a challenge at the feet of the artist. We – as creators and manipulators of visual symbols – have a significant role to play in disrupting those oppressive power structures.

In response to the symbolic violence that has been aimed at women through much of Western art history, I aim to remake the image of woman. I work within the tradition of European oil painting in a subversive way; it is possible to hold a deep love and respect for that tradition, whilst engaging with it in a critical manner. I want my work to speak on an historical level, whilst being contemporary in its stylistic cues and mode of expression.

The biblical narrative of Salome is that she dances in exchange for the head of John the Baptist. Salome was a popular subject for Renaissance painters, who fetishised her beauty whilst taking a stance of moral superiority by signalling indignation at her actions.

The femme fatale is a persistent chauvinistic trope which identifies female sexuality with manipulation. It suggests that women’s power lies in their beauty, but that power should not be released or allowed to become active, only admired in its passive state.

In this painting the top of the canvas shows an advert depicting a female head and at the bottom of the canvas is a shopping bag containing a male head. These heads are an extension of Salome; her own face intersects the space between the two, between the idealised and the grotesque. The image of female beauty in advertising can be seen as a manifestation of symbolic power ultimately not owned by herself, and so it appears here as a death mask floating on the surface, a lure. The male head is not proudly presented; it merely sits in the carrier bag like a head of lettuce, as if casually bought on the commute home. In contemporary society, graphic violence has become almost boring, whilst structural violence bubbles away under the surface of seemingly innocent idealised images. My female protagonist exists within this reality, but unlike the two other heads, she faces forwards and is shown in thought, as if picturing a different future.

Minjoo Kim | Full Moon Party

This narrative was inspired by the annual Full Moon Party in Koh Samui, Thailand. Especially the image of what happens after the party. The image of countless drunk western people lying around on an eastern island strongly intrigued me. In this painting, I put myself in the middle of the scene, wearing and doing something inappropriate to present my feeling of isolation in a strange world.

As a person who had always belonged to the monocultural society in South Korea, since moving to London in 2016, I’ve realised that I’m now being categorised by more diverse social groups than before. This has led me to indirectly experience all the current diversity issues of race, nationality, religion and gender more than ever, together with the silent anger that lies underneath it. I wanted to depict the irony of the fact that a ‘multicultural’ city is always the best place for this research.

Kaveh Ossia | Repress Yourself, Don’t Express Yourself

Repress Yourself, Don’t Express Yourself revolves around the concept of self-promotion and individuality. In recent years the politics of extremes have led to a rise of ideals of self-love, acceptance and identity in their bare, superficial and commercial form. High street businesses display rainbow flags (in all their diversity); TV shows, pop culture and entertainment industries tell us to love ourselves just as we are; and M&S brings out its LGBT sandwich (Lettuce, Guacamole, Bacon and Tomato to be precise).

Politicians remind the people of the glory days of the mythical past and sovereignty. One half of society hates the ways of the other, wearing badges identifying which side they are on, while simultaneously one makes sure one is (uniformly) individual.

In a time when leaders publish policies through a tweet and in a time in which weshare our life stories on our social media. In a time when everyone is encouraged to openly celebrate and cherish their identity. In a time in which the art world continuously pushes artists to disclose and discuss their identity in their work (especially if from a ‘shit-hole’ country that we all want to know more about). In these current times, it is extremely refreshing to me to wholly distance myself from my identity, not to fill in the blank and to withhold the details of my exotic and colourful biography. A moment of tranquillity amongst all the noise, a moment in which I repress myself and not express myself.

“when the people will have lost their

remembrance and thus will have

no past,

when they will have lost their need for

contact with others…

then they will live in a world of only

Colour, Light, Space, Shape and Movement

then Colour Light Space Shape Movement will be free

There will be Colour

Light

Space

Shape

Movement”*

* Adapted from Stanley Brouwn

Tai Tran | The golden thread #1

I’ve always been interested in the idea of myth and reality. As an immigrant, I’ve searched for a better life, as do nowadays thousands of refugees all over the world. But where does the truth lie?

Myths can turn into reality for some and reality into myths for others. Through my art practice, I aim to challenge the notions of myths and reality. I believe that art has a crucial role to play in transforming, redefining and reimagining reality.

Antonietta Torsiello | Drain

Being so weak, demoted yet defiant. You build your wall and decide this will not defeat you.

This work was inspired after hearing Mr Braithwaite speak at a resistance workshop on his activism since losing his job after 15 years of service as a teaching assistant. Michael is 66 years old, a dignified and gentle man, quietly spoken, a pillar of his community.

‘’The constant knot in my stomach’’ was something that stood out about his emotional state, which is why I decided not to decorate this work. It represents all of his value being stripped away from him after he had nurtured so many.

This work is dedicated to the more than 50,000 people who came with their parents from Caribbean countries between 1948 and 1971, who were suddenly losing their jobs and facing eviction, NHS bills and even deportation because they couldn’t provide the documentation proving their residency status.

Antonietta Torsiello | Last time

Having a personal connection to the Windrush scandal, my family member was threatened with deportation to Jamaica after living in the UK since the early 1970s. This work is a response to the hostile environment deportees and their families have been subjected to by the Government.

The materials are chosen to represent a symbol of today’s numb culture where human beings are seen as just a number, with no name or story attached. The work embodies the notion that you are disposable once you have been emptied of your valuable contents; humans discarded like throw away objects, suddenly becoming outsiders.

Robyn Litchfield | Arnold River

My paintings are representations of sublime encounters with places, pristine and untouched. I draw from archival material and personal documents relating to the early exploration and colonisation of New Zealand, aiming to reimagine and examine the experience of forays into a hitherto unknown space. I am interested in the idea of wilderness and the unknown as a terrain of the mind and as a place that induces reflexivity.

Most of my sources are photographs; mainly personal archival images of early New Zealand and, more recently, contemporary photographs of primeval landscape – mostly taken by me. I apply transparent paint in expressive brushstrokes and work back into it using various implements and processes such as scraping, layering and erasure to reveal the luminous ground below. The paint mimics the emulsion on the glass plates of early photographs whose images were revealed by light shining through them. I think of the ground like a screen where images are projected and perceived.

Stencil use was developed as a means to subvert other images, reproduce forms and create a visual vibration. By cropping and editing early postcard images of forest, I aimed to reveal the ‘punctum’ of the image. The dark red forms placed within this painting derive from remnants of stencils developed for these earlier works. For me they are symbols of loss; of past life, of primeval forest – the biodiversity that it supported and represents a lament for this loss. Their intrusion into the picture plane is a metaphor for a kind of otherness akin to that felt through the experience of immigration.

Sam Parsons | Time to act

Having trained as a zoologist, the natural world and its conservation is a key influence throughout Parson’s work. This piece gives a bird’s eye view of a fragile landscape using the random interactions between the media to give the appearance of organic growth.

The increasing awareness of the climate threat and the growing activism now taking place is encouraging, however, the progress in halting the degradation of our planet is still too slow.

The price tag of this work acts to stress the urgency of our situation, and how serious action is needed to focus our money and efforts to where it is most required. The painting also serves to draw attention to and raise funds for World Land Trust, a charity which acts to protect entire ecosystems by purchasing land to turn over to conservation. Should this painting sell an area not far off the size of central London could be protected and treasured for future generations.

Please listen to Greta Thunberg

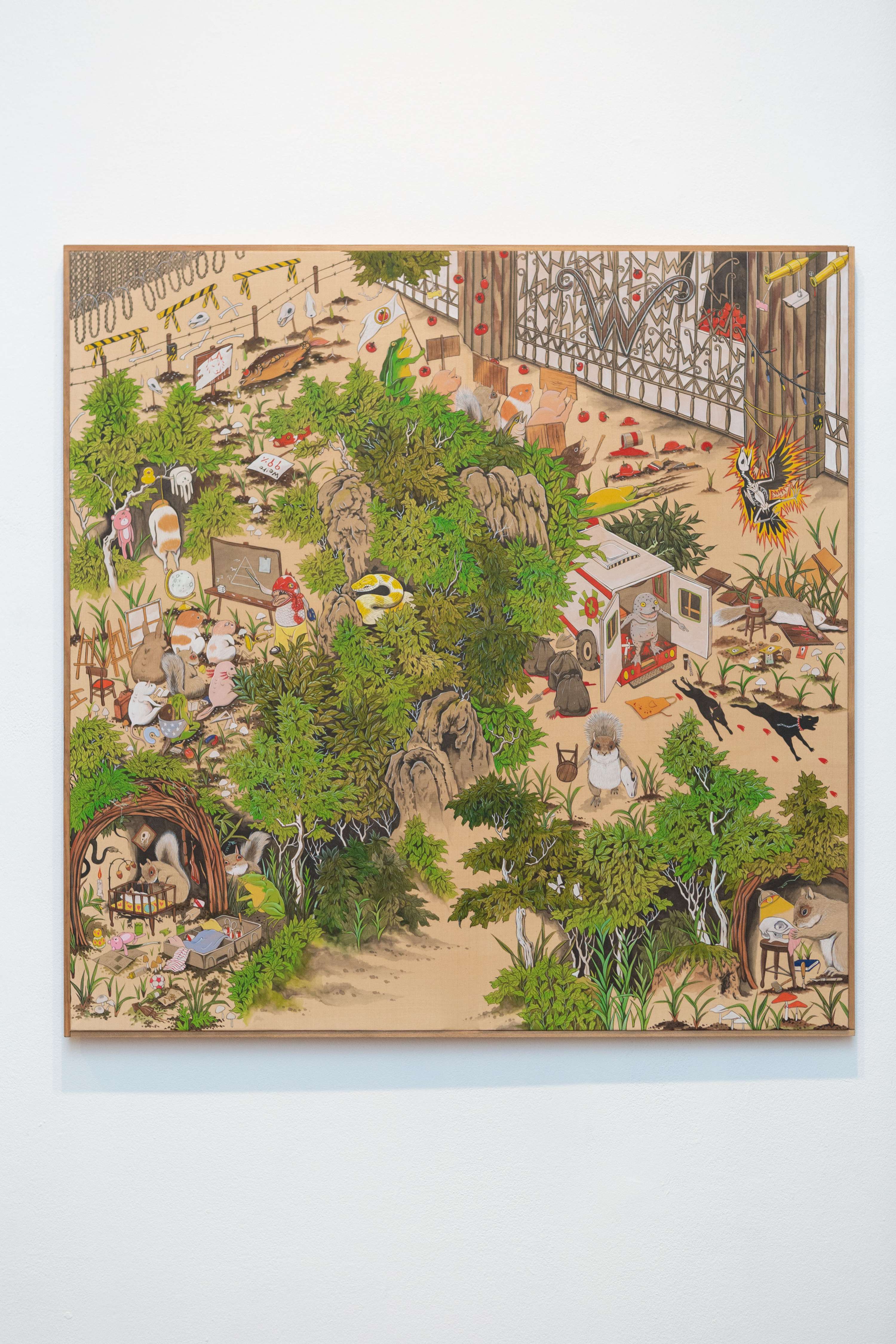

Hun Kyu Kim | Soon, life will become more interesting

I craft precise allegorical pictures, employing a range of political, contemporary, and art-historical references and influences. Through my application of oriental painting, I build intricate stories about an imaginary world. Yet this fictional world becomes an analogy for my interpretation and reflections on the very real recent political situation in South Korea and its startling transformation since a stamping out of a corrupt regime.

I am a very typical artist who inherits the spirit of the Candle Light Revolution of South Korea in 2017. Observing recent political changes in South Korea, I attempt to reconstruct the way that numberless political artists have paved for the tradition of the oppressed through my subtle fantastic world. To grasp a hidden meaning inside of mundane objects, I frequently borrow diverse cultural references such as pop culture, SF film, cartoons, or even historical facts, rebuilding my imaginary world where a strict boundary between the myth and the reality becomes diluted. Therefore, I define myself as a storyteller.

Images of fragmented and scattered narratives spread across the world and they start to be tangled together. Each story is working as an independent entity, but shares a common world full of imagination, making another narrative. With the exquisite dialectical allegory, each story shows a special fantasy to reflect on the barbarism hidden behind the seemingly innocuous material affluence of contemporary society where Capitalism and Neoliberals become a form of religion

As Candle Light Revolution turned out to be the most successful and peaceful political movement, likewise, I consider my artistic practice as a mode of non-violent political action and believe that the recent situation in South Korea can act as a fragmented blueprint for something more global. People should feel encouraged to keep fighting to make positive changes in the world around them.

Marcus Orlandi | Man Sandwich

Man Sandwich is a reflection on the entitlement, self-gratification and pomposity of toxic masculinity, paraded so effectively by current prominent figures such as Boris Johnson, Piers Morgan and Donald Trump. The work hangs high on the wall so it’s looking down at you or, more significantly, so you are looking up at it. It’s grotesque and disgusting and absurd, much like the aforementioned trio.

The work was partly inspired by the right-wing jibe “make me a sandwich” used often by men/trolls online when commenting on opinions that offend them, such as equality, women’s liberation or feminism. This is a cod piece for their most sensitive area, as clearly it needs protecting. They are such delicate flowers. The work is made from cheap and discarded materials, papier mache and recycled cardboard; an attempt on my part to salvage some of the waste in the world. Probably something that would irritate the trio if they found out.

The work is for sale at £100,000 just so it upsets Piers Morgan if it sells. Get out your cheque book.

Fleur Yearsley | To The Moon And Back

When I was six years old, dad made a cardboard rocket for my sister and I. Looking up at the construction with awe we fully believed we were going to space with the power of our imaginations. Rather than being indulged with the latest overpriced toy or expendable product, the enterprising and creative spirit of my dad turned rubbish into a trip to the moon and back.

I paint from my own elusive but potent memories. Painting facilitates a way for me to revisit, grasp and sincerely depict certain recollections and capture their sensuous qualities. Taking the bare essentials and what is necessary from personal experience, my painting is structurally considered and refined with colourful sensibility. In a world often imbued with exclusivity, I use the materiality of paint to instil humanity into each subject matter by working through personal and collective histories and relationships.

The abundance of images and information today can be challenging to process and navigate in a society that is constantly moving. We can feel a separation not only from ourselves but also from others, as there are more and more distractions to keep us occupied. It is easy to lose sight of whom we really are and the fact that our memories are what make us.

Anita McCullough | After the wildfires, Wanstead Flats

Most of the medieval ‘common’ land of England has been lost due to enclosure and, in our own century, the treasured spaces that now remain are suffering new threats. Among those spaces is London’s Epping Forest, characterised by a diversity that includes deciduous woods, wild heath and grassland habitats. These feature rare species of flora and fauna, from insignificant spiders and flies to the migratory birds that see fit to enrich our lives with their flighty songs in spring and autumn.

When the worst wildfires ever experienced in the Greater London area ravaged Wanstead Flats in mid-summer 2018, the effects of global climate change were felt profoundly in our locality. The fires raged over several areas, including one of special scientific interest. The eco-system suffered damage from which it will take decades to return – and the fire came at a bad time. Over-zealous management by the forest’s guardians, the City of London Corporation, in the previous spring (and the one before) had already denuded precious natural habitats and rendered former safe places for wildlife non-existent. There was more behind the ‘clearances’ than met the eye; this work was more than the seasonal pruning of old.

My work has always been a response to the natural world, and now what is happening on my own patch has become my focus; anthropogenic impact came home. I went from celebrating the verdant to needing to express my anxiety over the potential of the forest (and the flats in particular) to regenerate after what felt like a double assault. The rain could not come a day too soon after that arid June and July. It was a while before the green shoots began to appear. They came in the form of mosses and sedges atop the remaining charred anthills; too many of these had already been flattened by man. Small shoots emerged from the blackest of black-sootiness that printing ink surely could not replicate. Yet I gave it a try and a series of woodblock prints resulted. The one you see here heralds the sunrise and a beneficent shower of rain to one of the hardest-hit sites. A slow, fragile recovery is now in progress, but pressure from the activity of thoughtless humans is still all too apparent.

Melitta Nemeth | Bare memory 2

My painting was inspired by a photo I made during one of my visits to my hometown, Budapest. It was created in 2016 just before the EU referendum and it captures the desire to escape current reality (space and time).

I left Hungary to live in London in 2013. While living in voluntary exile, one has to think about what to bring with them, what to keep physically, mentally and emotionally. The meaning of home becomes problematic.

After growing up and living in a city where every street and corner brings up a memory, you wake up in another place where you can’t tell one house from another because you don’t know them. Consequently you keep remembering the familiar place and start to idealise it.

My intention was to show the city, but to hide it at the same time. I used the shape of a tree, as a metaphor of time, to cover the cityscape. Memory works similarly in a selective way; we remember certain moments and details of the past, others we forget or might only imagine. The past can seem inaccessible and intangible. The tree finally encloses the details of the city itself, like an inclusion in a rock that contains fossils of another age.

Almudena Romero | Performing Identities

Performing identities is a series of wet collodion passport-looking tintypes. The series revisits this historically significant photographic process to address links between photography, identity and colonialism, specifically looking at how photographic archives have contributed to the construction of national identities and the consequent notions of us and the other.

Using the main photographic technique of the Victorian era, once used to write and exclude the history of society, the work aims to leave a legacy of a contemporary understanding of identity, photography and artwork production from a decolonial perspective. Enforcing this is the reliance on the dynamics of mutual benefit, interdependence and collaboration between the artist and participants involved in the production of the series.

Started as part of Refugee Week in 2017 and coinciding with Almudena’s own tenth migrant ‘anniversary’, Almudena invited people in her social network to come to her studio and participate in a series that related portraiture with migration. Participants needed to consider themselves immigrants before agreeing to participate. Therefore the production of artwork relied on the participants’ initiative to a) see themselves as immigrants and b) take the time and energy to come to the studio and do a tintype. This interdependence between the artist and the participant/performer was reinforced by a mutual-benefit dynamic. Each participant was welcomed to stay in the studio, learn about the collodion process and received a copy of their tintype. From this participatory/performative approach one's national identity is a fluid notion, and it's up to the performer/participant to embrace one perspective or another, rather than the artist to establish views on others.

The resulting outcome is an archive of 200+ tintype portraits of arts related people based in London who would see themselves as immigrants, including Almudena herself; an archive of performed self- biographies.

Lorna Pridmore | Untitled (for now)

Untitled (for now) is made using a prolonged process of de-constructing and re-constructing the individual threads that make up a remnant of hessian fabric. Slowly pulling away selected sections of the coarse material by hand, it becomes a precarious balancing act to ensure it stays intact and does not unravel to the point of collapse.

Hessian is generally used to make sacks or to underpin upholstery; both purposes act as ‘supports’ for everyday life: to help us carry heavy loads or to hold us steady and firm on the padding of sofas and chairs. Systematically un-ravelling the warp threads hidden beneath the surface weft of the fabric becomes a precarious act of change. Pridmore is interested in working intensively with material to reveal its inner depths – light or dark, literally or figuratively – by creating new forms for broader philosophical interpretation. Using simple actions such as pulling, wrapping, clipping, binding or pinning, an ordinary and often ignored ‘thing’ is reformed into a new ‘other’; making us question our intuitive logic and perceptions as a means to reconsider the general orchestration of the world around us.

Miraj Ahmed | Go On, Say It.

We are living in a time in which we are overloaded with images and words. Slogans, buzz words, signs, hate speech, fake news, lies, cliché and rhetoric. Yet we struggle to find agreement or consensus. Truths are spoken but ignored or censored. We understand and misunderstand at the same time, speak in turn and out of turn. I’m hoping that this painting speaks for itself.

“Memory is always incomplete, always imperfect, always falling into ruins; but the ruins themselves, like no other traces, are treasures: our guide to situating ourselves in a landscape of time”

Rebecca Solnit The Ruins of Memory

Looking at ideas around time and memory Tower is an ephemeral image, reminiscent of a fragile Tower of Babel. In this way it is a structure that is on the verge of collapsing or fading away, something that is reflective of current tumultuous political times; a structure that no longer has solidity but is unsteady and dissolving into a maelstrom of ideas and noise. Tower is landscape as a psychological space, a reflection of a sense of place and the struggle to find our place within.

Nye Thompson | INSULAE (Of the Island)

Flying at drone height over virtual waves, Thompson's video installation INSULAE contemplates the impact of island geography on national identity in the age of Brexit. This installation, which comprises of approximately six hours of video, presents a perpetually looping virtual tour of the waters just off the British coastline and circles the entire mainland. With the ocean as a metaphorical buffer between the UK and the rest of the world, the viewer is taken on a digitally-rendered journey, endlessly patrolling our watery borders.

For me the Brexit movement has deep roots in our island geography, the buffer of ocean which has historically isolated, insulated, and also protected us from mainland Europe. British imperial ‘greatness’ – and all the nationalistic nostalgia that idea inspires – largely stems from this strategic advantage of being surrounded by a coastline filled with accessible warm water ports. So this video is a way of talking about our sense of nationhood in a post-Brexit environment.

Nye Thompson

Created using Google Earth – initially developed as a CIA global surveillance tool – this video is very much an artificial construct, like any historical narrative. Artefacts and glitches become incorporated into the visual narrative; fleeting moments are frozen, distorted and monumentalised; and the whole vision digitally filtered, enhanced and artificially beautified. The deeply emotive concept of a national border is re-framed aesthetically through the distancing god-gaze of satellite imagery.

Victoria Burgher | Surviving

The ubiquitous media images of shipwrecked migrants wrapped in shiny golden shrouds tell only a small part of the story of forced migration. They ignore the horrors of people trafficking and the hazards of perilous sea crossings made to escape war, persecution, poverty and climate change.

Surviving is an installation made from fragments of a gold foil survival blanket cast in imperishable ceramic, laminated in goldleaf, and displayed in the form of archaeological shards. The work aims to represent the strength and tenacity of these people, while recognising their vulnerability and fragility when at the mercy of the sea. Real gold is used both to revalorise the worth of those traded like currency by people traffickers, and to highlight how neo-colonial capitalism ignites the geopolitical conflicts that force people to flee.