The village of Aberfan is defined by the tragedy that unfolded in 1966. No mention of Aberfan is possible without reference to the collapse of the colliery spoil tip; the deaths of hundreds could have been prevented with sufficient environmental management, a common theme throughout the history of Welsh mining. The South Wales Coalfield was regarded as having the worst safety record of British coalfields between 1850 and 1930. Insufficient safety precautions and poor management during this period, in which mines were being sunk to new depths, resulted in the deaths of over 3,000 men.

The towns of South Wales expanded rapidly in the 19th century with the conception of coal mines throughout the region. Once sparsely populated, the character of these towns and villages would become defined by their relationship with coal. Glamorganshire’s population swelled by 330,000 as workers moved from Northern Wales and the neighbouring English counties in search of employment. By 1921 the coalfields would employ over 250,000 men. This peak was followed by a steady decline as the demand for coal from abroad declined and processes of mechanisation were implemented. A population decline was inevitable as the unemployment rate climbed. Unemployment in Merthyr was the fifth highest in Britain, with half of all people in the region battling against poverty. Profitability had dropped to record lows. The mines had transitioned from profit to loss in the space of 3 years. Miners were asked to work for less money, whilst fulfilling longer hours, in a desperate bid by mine owners to break-even. Insulted by these demands, miners began to strike. The action would last for much of 1926, until the miners were forced into accepting the stipulations of the government. These included lower wages and increased hours. Communities suffered with the decline of infrastructure; the focal points of colliery towns withered as populations continued to decline.

From 1920 to 1950, populations of mining towns in Wales continued to recede. There were difficult years between 1918 and 1939 in which nationalisation was seen as the dawn of a new era. The National Coal Board (NCB) would close 34 pits in South Wales, with focus drawn to bigger production collieries.

Claiming the lives of 116 children and 26 adults, the Aberfan disaster was one of the worst mining incidents to occur in Britain. The gross negligence of the NCB was solely responsible for the level of destruction caused by the collapse of the tip. Mist shrouded the hillside, making it unclear exactly what was unfolding above the village. The site of the tragedy, Tip 7, had been started in 1958. Unique for this mine, the latest tip included tailings; the fine particles left after the chemical filtration process that separates the coal. The addition of tailings in the spoil changed the consistency of the materials; the slurry had become like quicksand. As the tip moved down the mountainside, it destroyed two farm cottages and its inhabitants. It then consumed the junior school and 18 houses. All of which were engulfed in the landslide. The timing of the disaster coincided with the morning classes at the school. Children were trapped; the headmistress died in her study; an assistant was killed taking dinner money, yet her body shielded 5 children from death. School children were aware of the imminent danger, as the landslide created a sound similar to that of an earthquake. Light through the windows disappeared as the wall of black silt swept away the school walls. In total, 109 children and 5 teachers died at Pantglas Junior School. The accounts of these young survivors contextualised and humanised the terror of the landslide.

The price of coal; the willful ignorance of those in charge had decimated a generation. When emergency services arrived in Aberfan, so too did the media. The BBC coverage appealed to thousands of volunteers who rushed to the Merthyr Vale, at times hindering the progress of experienced miners. Survivors were pulled from the rubble within the first hour. Victims who were buried for longer had suffered from asphyxia. Famously, Harold Wilson and Queen Elizabeth conducted visits to the village. The royal visit coincided with the final stages of the initial clear-up, a day after the final unaccounted for body was found. Wilson was in communication with Lord Robens, the chairman of the NCB, who failed to act with haste in the immediate aftermath. Instead of attending the site, he attended an award ceremony at the University of Surrey. This would serve as further evidence of the negligent NCB, compounded by the discovery of letters from concerned local people. Their letters should have served as ample warning to safeguard the village. In 1965, concerned residents petitioned, and the accumulated signatures were sent to Merthyr Borough Council. No action was taken. The National Coal Board were held accountable; her Majesty’s Inspectorate deduced that they would have to provide training to ensure tip safety. They would also have to provide plans on tipping to local authorities, who could contest the safety and utilise an independent decision making authority. These reactive measures would change workplace health and safety measures for decades to come. Those responsible for the mine were never prosecuted.

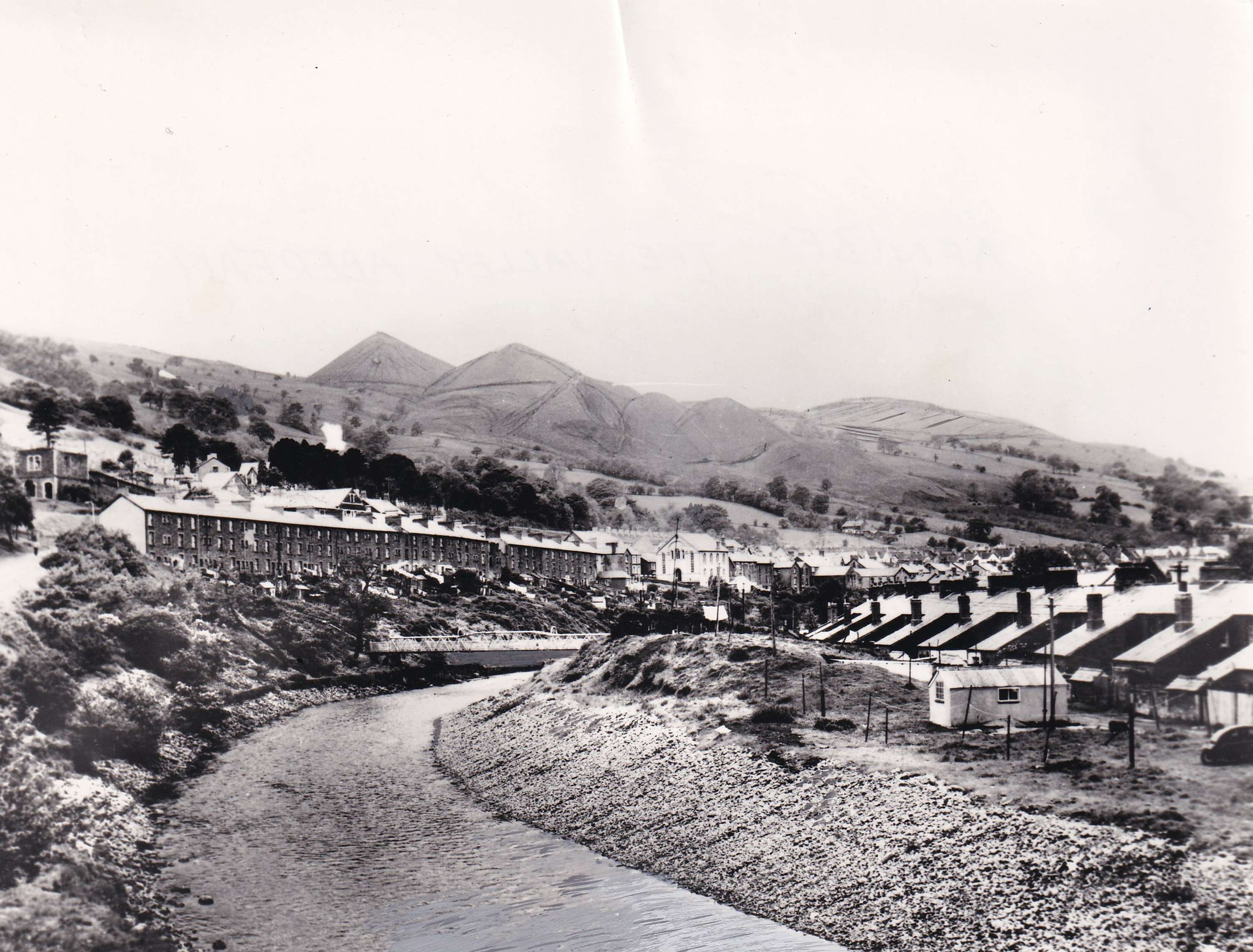

Monetary support for the people of Aberfan poured in over the immediate months. Some of the funds were distributed between bereaved families, paying for funeral costs and repairs to damaged homes. Distraught parents were offered £50 as compensation, though an outcry saw the sum raised to £500. An amount the NCB deemed to be ‘a good offer’. Financial repayment was of little concern to the families of Aberfan, who were contending with significant psychological turmoil. The trauma of the incident was exacerbated further by those in control of the Aberfan Disaster Fund, when it was decided that financial compensation would not be paid for those physically uninjured. This was despite claims of post traumatic stress, paranoia and anxiety. A local doctor proclaimed that ‘by every statistic, patients seen, prescriptions written, deaths...this is a village of excessive sickness’. The landscape of Aberfan was a tremendous concern after the disaster. A repeat incident, featuring one of the neighbouring tip sites, was a possibility. Policy change included the need to smooth the unsightly tips. The planting of grasses and small bushes would eliminate the danger of further slips and improve the appearance of the valley. Despite this, the threat of a landslide still survives today.

Over 50 years have passed since the tragedy of Aberfan. The damage to the landscape and community is still evident. The disaster fund has been instrumental in maintaining a cemetery and memorial garden, once the site of Pantglas School. It serves as a reminder of the unjust treatment that was delivered upon the men and women of Aberfan, the ‘appalling calamity’ of the landslide that could have been avoided. The Merthyr Vale colliery closed in 1989, though the tips still stand today.